Defining Placemaking

The not-for-profit organisation Project for Public Spaces (PPS) was established in 1975 and is one of the earliest organisations to implement placemaking principles. They state ‘Placemaking is community-driven; visionary; function before form; adaptable; inclusive; focused on creating destinations; context-specific; dynamic; trans-disciplinary; transformative; flexible; collaborative; and sociable’ (PPS 2012). Mark A. Wyckoff, FAICP (2014). says ‘Placemaking is the process of creating quality places that people want to live, work, play and learn in’. However, placemaking is a broad term that encompasses various strategies to improve physical places and social connections, contributing to economic prosperity, and thriving communities (Rauch-Kacenski, Goldman & Hollander 2020).

Types of Placemaking

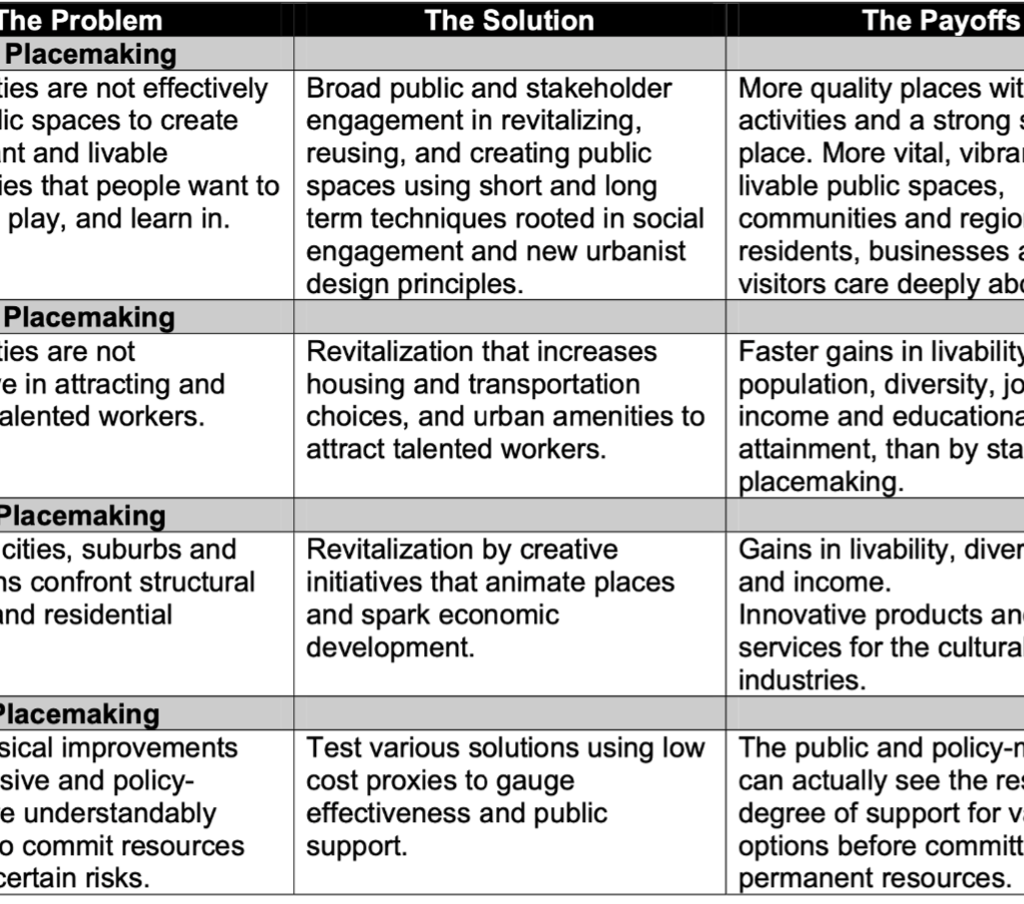

Wyckoff defined four types of placemaking, which are standard, strategic, creative, and tactical placemaking (Wyckoff 2014). They can be applied based on different place’s problems to provide suitable solutions and achieve the desired payoffs (Table 1) (Wyckoff 2014). Mahyar Arefi (2014) identified the relationships between people and places, and stated need-based, opportunity-based, and asset-based placemaking approaches in his book ‘Deconstructing Placemaking’. However, successful placemaking only happens when it is tailored to a specific community (Arefi 2014). Community-driven placemaking allows the community to carry out multiple placemaking approaches and strategies, and take advantage of them to achieve community goals (Arefi 2014; Wyckoff 2014; Rauch-Kacenski, Goldman & Hollander 2020).

Table 1 – Comparison of four types of placemaking

Fundamental placemaking principles

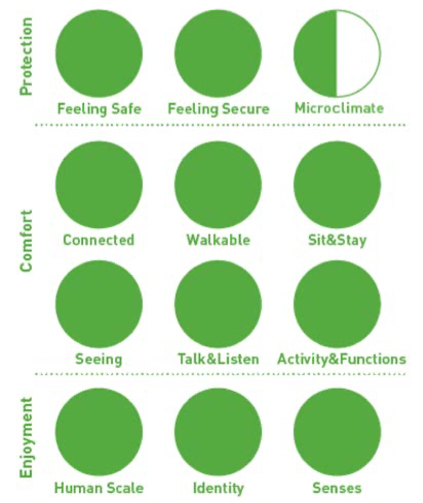

Evidence-based studies on the principles of placemaking have been developed by several organisations and researchers (Carmona 2013; Grabow 2015; PPS 2018; Rauch- Kacenski, Goldman & Hollander 2020). The organisation PPS has identified various placemaking principles in the last 15 years, which include but are not limited to 8 principles for innovation of placemaking, 11 key principles for creating quality community places, 10 principles for successful public squares, and 5 principles for media outreach (PPS 2005, PPS 2008, PPS 2016, PPS 2018). University of Wisconsin Professor Steven H. Grabow (2015) has examined placemaking principles based on five different functions of community areas and has provided evidence supporting these placemaking principles, which include principles for achieving effective and functional physical configurations, user-friendly and efficient circulation, preserved natural and cultural resources and environment, enhanced local identity and sense of place, and attributes to instinctively draw us to places. Architect, planner, and researcher professor Matthew Carmona (2013) emphasised that placemaking principles should be incorporated in developments in support of design principles. However, the most fundamental placemaking principle is that the community is the expert because people who form the community know more about their needs and challenges than anyone else possibly can (PPS 2009; Day 2012; Rauch-Kacenski, Goldman & Hollander 2020).

Implementation of Placemaking

Different scales of placemaking projects require a corresponding implementation framework (Drachen et. al. 2019; Place agency 2019). Small projects generally involve fewer numbers of people, lower costs, take short time, and are more flexible (Drachen et. al. 2019), such as the artist Chris Trotter art installation project in Brisbane (Place agency 2019). Large-scale projects are more complex, have higher costs, take more time, for example, placemaking in Liverpool One, Liverpool, UK (2004-2008) (Drachen et al. 2019; CBRE 2017; Place agency 2019).

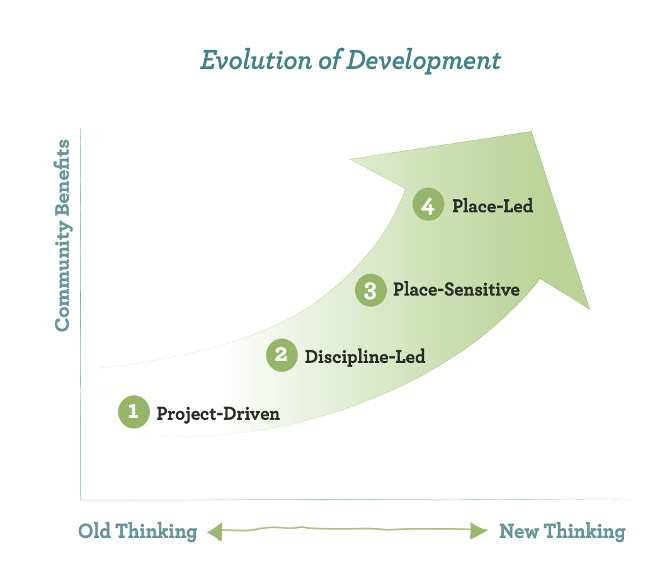

To successfully create a place, five implementation strategies need to be considered: governance, stakeholders, resources (such as funding), timeline, and maintenance (Drachen et al. 2019; Place agency 2019). Landscape architect and urban designer John Mongard claims that ‘these are best implemented through a networked planning and design process which involves collaborative design incorporating all types of engagement with users and dwellers’ (Drachen et al. 2019). Drachen et al. 2019 think the engagement of the place user and place context, funding and time management, and a commitment to the values of the place are very important to successfully implementing placemaking. PPS (2018) found that a place-led approach focus on place outcomes built on community engagement could benefit communities more than a project-driven, discipline-led, and place-sensitive approach (Figure 1). Therefore, successfully implemented placemaking needs to identify a suitable framework based on the project scale and ensure all types of engagement from the community.

Figure 1 – Evolution of placemaking

Impacts and Benefits of placemaking

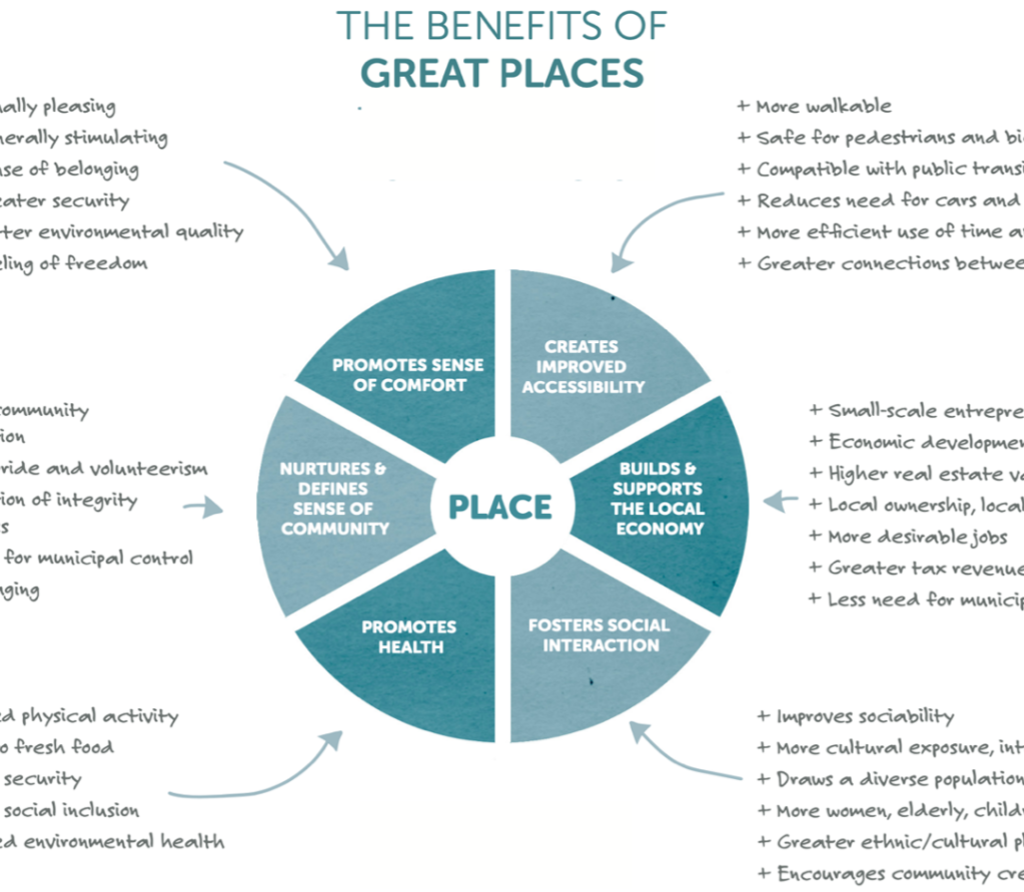

Successful placemaking creates great places that can promote a sense of comfort, create improved accessibility, benefit the local economy, foster social interaction, and nurture a sense of community (Johnson, Glover & Stewart 2014; PPS 2018) (Figure 2). It can transfer a place to a destination. It can enhance people’s health and well-being, bring pleasure and inspiration to people while increasing property value. Federation Square, Melbourne is one of the successful examples (PPS 2012; CBRE 2017; Fortuzzi 2017) (Figure 3). But, like William H. Whyte said, ‘It is hard to design a space that will not attract people’ (PPS 2009).

Placemaking is not only about designing public spaces but includes management of the place or place-keeping (Dempsey & Burton 2011; Fortuzzi 2017), for example, when vandalism, litter, and damage to facilities occur, people may feel uncomfortable and insecure (Dempsey & Burton 2011). Place-keeping not only encompasses physical environment, place design, and maintenance but includes partnerships, governance, funding, policy, and evaluation (Dempsey & Burton 2011). Therefore, places can always be improved, and the process can always be continued (Fortuzzi 2017).

Figure 2 – The benefits of great places

Figure 3 – The outcome of placemaking in Federation Square, Melbourne

Measurements of placemaking

Placemaking projects begin from developing a set of indicators that help better measurement and understanding of the outcomes of placemaking (Treskon 2015; Morley & Winkler 2014). One size does not fit all when it comes to identifying placemaking indicators because projects may have multiple and varying goals (Morley & Winkler 2014). These goals will be dictated by placemaking types, place functions, placemaking project scales, and the needs and challenges of communities for urban public spaces. For example, digital placemaking gains business traction through customer engagement and online marketing (Placemaking group 2020). But increasing employment opportunities and reducing crime may be considered as creative placemaking and are community indicators (Morley & Winkler 2014). After setting up project indicators based on the aims of each individual placemaking project, social data selection and analysis helps tracking the outcomes of placemaking and its success (Christiansen-Franks 2019). A post-analysis, interviews with stakeholders, and comparing the current project with other similar projects also help in measuring the outcomes of placemaking projects (Treskon 2015).